The art conservation world is reeling from a groundbreaking study that utilized ultraviolet light examination to assess restoration work on historical oil paintings. The findings, which have sent tremors through museums and auction houses alike, suggest that a staggering 80% of examined artworks show signs of excessive intervention during previous restoration attempts.

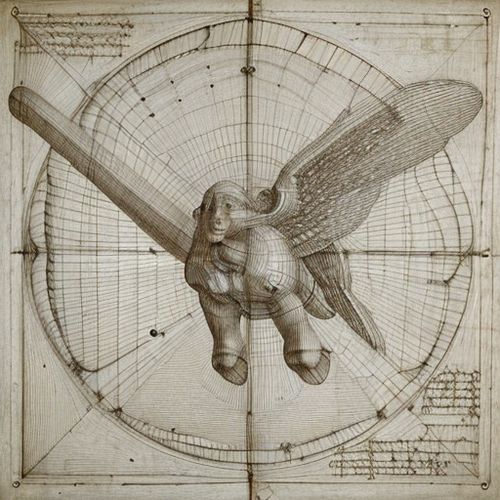

For decades, art restorers have worked under the assumption that their interventions were both necessary and minimal. However, advanced UV imaging techniques now reveal the startling truth beneath layers of varnish and retouching. What appears flawless to the naked eye often conceals aggressive overpainting, irreversible alterations to original brushwork, and in some cases, complete reworking of compositional elements.

The Science Behind the Scandal

Ultraviolet fluorescence photography has emerged as the most powerful tool for detecting restoration work invisible under normal lighting conditions. When exposed to UV light, original materials and later additions fluoresce differently based on their chemical composition. Original varnishes typically glow a warm yellow, while modern synthetic materials appear cooler and more intense. Overpainting becomes glaringly obvious as dark patches that absorb rather than reflect UV radiation.

Conservation scientists developed a standardized scoring system to quantify restoration extent. Paintings showing more than 40% surface area with non-original material were classified as "excessively intervened." Alarmingly, four out of five works crossed this threshold, with some Renaissance pieces displaying up to 90% overpainting in certain sections.

Case Studies That Shook the Art World

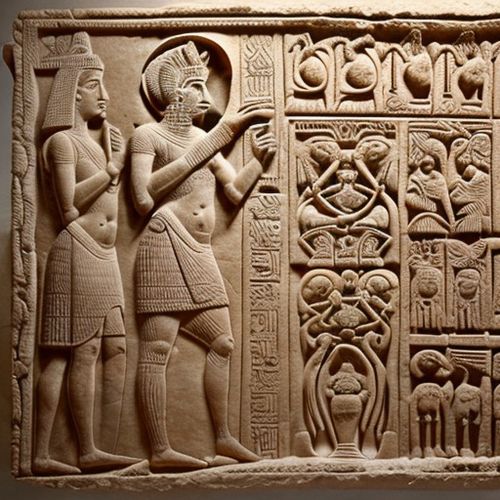

Among the most shocking discoveries was a supposed "pristine" Caravaggio in a European private collection. UV examination revealed that nearly the entire background had been repainted during the 1950s, completely altering the artist's intended spatial relationships. The dramatic chiaroscuro effect for which Caravaggio became famous had been artificially enhanced by later hands.

Another bombshell involved a major museum's prized Rembrandt portrait. What appeared as subtle aging cracks under normal light transformed into a spiderweb of overpainting under UV, with entire facial features reconstructed during an undocumented 19th-century restoration. The current version bears only passing resemblance to infrared images showing the original underdrawing.

Why This Matters Beyond Conservation Circles

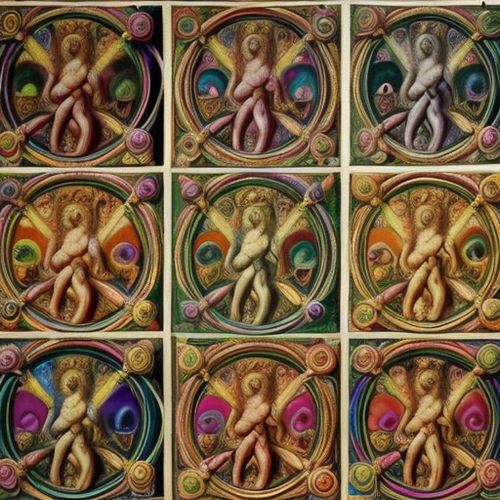

The implications extend far beyond technical debates among conservators. Auction prices, museum attributions, and even art historical narratives may need reassessment. Many "well-preserved" masterpieces turn out to be collaborative works between the original artist and generations of restorers. The very definition of authenticity in classical art requires reexamination.

Legal ramifications are already emerging. Several collectors have initiated lawsuits against auction houses that sold paintings described as "in excellent original condition." Insurance companies are scrambling to adjust their appraisal methods, as over-restored works may carry significantly different risk profiles and valuations.

The Human Factor Behind Over-Restoration

Interviews with veteran conservators reveal multiple causes for this epidemic of over-intervention. Mid-20th century restoration practices favored making paintings look "fresh" for contemporary tastes, often at the expense of historical accuracy. Pressure from collectors and museums to present works in a "flawless" state created perverse incentives. Some conservators admitted that job security sometimes depended on making dramatic visible improvements rather than minimal, reversible treatments.

Compounding the problem was the lack of standardized documentation. Many restoration records from the 1930s-1980s either weren't kept or were deliberately vague about intervention extent. The introduction of synthetic varnishes and acrylic paints during this period created materials that initially matched originals but aged differently, making earlier overpainting invisible until modern UV analysis.

A Path Forward for Art Stewardship

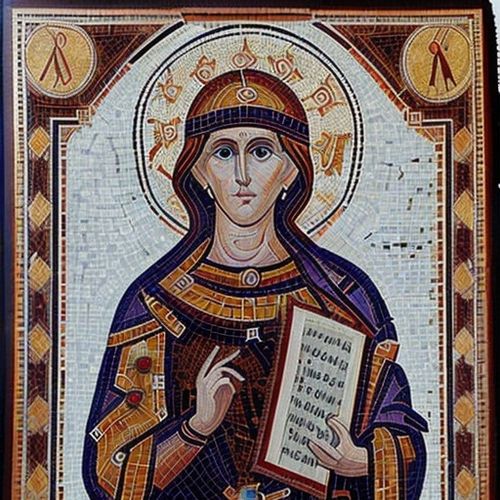

Leading institutions are already implementing reforms. The Getty Conservation Institute has pioneered new ethical guidelines emphasizing documentation, reversibility, and respect for original material. Some museums now display UV examination images alongside restored paintings, allowing viewers to distinguish between original and restored areas.

Technology offers partial solutions. Multispectral imaging creates "restoration maps" that future conservators can reference. New reversible synthetic materials allow for more ethical retouching. Perhaps most importantly, the art market is beginning to value honest conservation reports over superficial perfection.

As one senior conservator at the Louvre remarked, "We've entered an era where transparency matters more than appearances. The goal isn't to make paintings look untouched, but to ensure they remain truthful witnesses to their own history - including all the human hands that have shaped them."

By Daniel Scott/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 12, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025