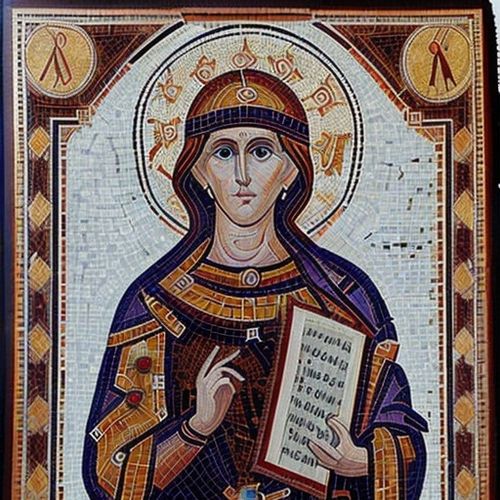

The ancient walls of St. Michael’s Cathedral had borne witness to centuries of whispered prayers, flickering candles, and the inevitable accumulation of grime. For over a hundred years, layers of soot and smoke from incense and candles had dulled the vibrant frescoes adorning the chapel’s ceiling, obscuring the intricate brushstrokes of master artists long gone. Then, in a remarkable fusion of art and science, conservators turned to an unconventional solution: sound waves.

The breakthrough came after years of painstaking research into non-invasive cleaning techniques. Traditional methods—chemical solvents, abrasive tools, or even laser cleaning—carried risks of damaging the fragile pigments beneath the grime. But ultrasonic technology, originally developed for industrial and medical applications, offered a delicate alternative. By calibrating high-frequency sound waves to vibrate at precise intensities, conservators found they could dislodge centuries of dirt without so much as grazing the paint beneath.

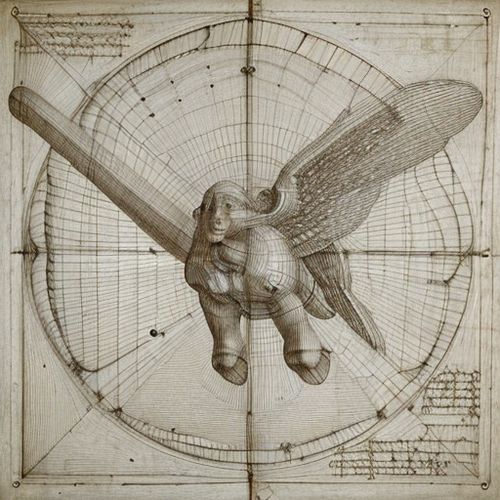

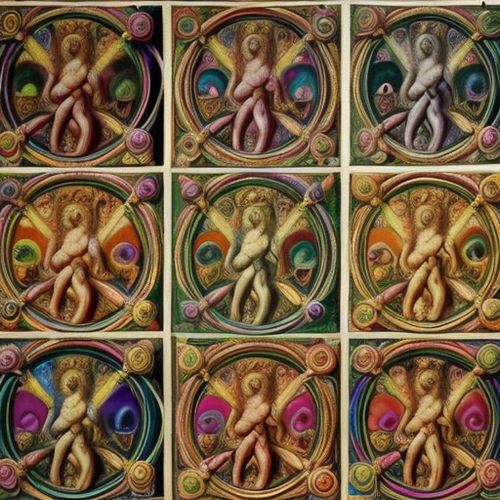

The process was as meticulous as it was innovative. Specially designed transducers emitted controlled sound waves that traveled through a fine mist of purified water sprayed onto the surface. The vibrations created microscopic bubbles in the liquid, which imploded with just enough force to lift away the soot particles. What emerged from beneath the grime was nothing short of revelatory: scenes of saints and angels, their colors as vivid as the day they were painted, untouched by time or the well-intentioned but heavy-handed restorations of previous eras.

Dr. Elena Moretti, lead conservator on the project, described the moment the first section was cleaned as "like opening a window into the past." The team had expected improvement, but the sheer clarity of the uncovered details—the subtle shading of a robe, the glint of gold leaf in candlelight—left even seasoned experts momentarily speechless. Word spread quickly among art historians, and soon cathedrals across Europe were inquiring about the technique.

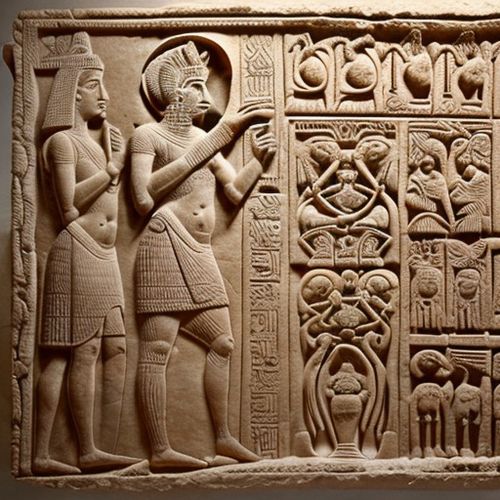

What makes this achievement particularly significant is its broader implications. Countless artworks worldwide suffer from similar degradation, especially those in religious or historic buildings where smoke and environmental pollutants have taken a toll. The success at St. Michael’s suggests that ultrasonic cleaning could be adapted for everything from medieval tapestries to delicate manuscripts, offering a gentler alternative to conventional methods. Early trials on marble sculptures have already shown promise, with sound waves removing black crusts of pollution without eroding the stone beneath.

Critics initially questioned whether the technology might have hidden drawbacks—perhaps vibrations causing microfractures in aged plaster or pigments. But rigorous testing on mock-up surfaces mimicking the cathedral’s walls put most concerns to rest. The key, researchers found, lay in the exact calibration of frequencies and the use of distilled water as a medium, which prevented any chemical interaction with the original materials. Monitoring equipment detected no structural stress during the procedure, only the steady retreat of grime.

As the work at St. Michael’s nears completion, the restored frescoes have become more than a conservation triumph—they’ve sparked a dialogue about how we preserve cultural heritage in the 21st century. The cathedral’s caretakers now plan to install advanced air filtration systems to slow future soot accumulation, combining cutting-edge prevention with their revolutionary cleaning method. Meanwhile, the team’s published findings have inspired collaborations between physicists, engineers, and art conservators, proving that sometimes, the best way to honor the past is to embrace the possibilities of the future.

The story of St. Michael’s frescoes serves as a reminder that some of history’s greatest challenges often yield to solutions we’ve yet to imagine. In this case, the same invisible forces that carry music to our ears or allow bats to navigate darkness have given us back a piece of our collective visual heritage. As sunlight now filters through the cathedral’s stained glass to illuminate the newly vibrant ceiling, visitors can’t help but feel they’re seeing the artwork—and perhaps the very idea of preservation—in a whole new light.

By Daniel Scott/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 12, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025